Have you ever had an idea for a project or business that seemed so good in your head, but just didn’t work out?

Have you ever poured your blood, sweat and tears into a startup that was doomed to fail?

Or are you currently working on a product, but you don’t know how to validate whether customers would actually buy it?

Chances are, you have. The vast majority of new ideas, product launches and startups fail. So how do you make sure that yours doesn’t? That your idea is not just another failure, but instead is: ‘The Right It’?

In the book The Right It — Why So Many Ideas Fail and How to Make Sure Yours Succeed, Alberto Savoia covers exactly that. A former director of engineering and Innovation Agitator at Google, Savoia has conducted a lot of research into what makes ideas work. The result is his book, which covers the processes you should use to determine whether your idea is a winning one — or is another failure.

The book is a superb starting point for starting entrepreneurs and anyone who wants to test an idea. So if you’re currently working on an idea for a product or service, and want to test it first before spending tremendous amounts of time and money in making it work, read a summary and book review of The Right It below.

Highlights of The Right It

The Right It starts with the idea that most startups are doomed to fail; something that Sevoia calls the Law of Market Failure. If you can find that one idea that actually works — that isn’t doomed to fail from the start — then that’s The Right It.

So how do you determine whether your idea is The Right It? By going through 4 different steps:

- Navigating Thoughtland

- Creating hypotheses

- Setting up a Pretotype, and acquiring YODA (Your Own DAta)

- Using The Right It Meter to determine whether your idea is The Right It

Navigating Thoughtland

Perhaps one of the most important concepts in The Right It is Thoughtland. Thoughtland is the place where only thoughts count.

At first, as an entrepreneur, you THINK that you have a great idea. And you THINK that your target group will buy your product.

So to test this, perhaps you run some qualitative research. You send a survey to your parents or even your ideal target group, and you get the results. Perhaps your target group indicated that you have a great idea on your hands. Your product is superb, and they will definitely buy it once you release it.

The problem with this research, is that we’re all still in Thoughtland. You’ve shared your product idea — not much more than a collection of thoughts — and people responded to your survey with a collection of their thoughts. But according to Savoia:

You cannot determine if an idea is The Right It just through thinking. Not through your thoughts — not through the thoughts and opinions of others. [Not even] through the thoughts of ‘experts’.

Rather, to truly determine whether your idea is The Right It, you have to get YODA to help you: Your Own Data.

Instead of using someone else’s market research, opinions, or success in the market, you can only test whether you have the right it if you gather data yourself. You have to get Your Own DAta.

So how do you do get YODA to help out?

Hypothesizing and Hypozooming

According to Sevoia, the first step is making a clear and specific Market Engagagement Hypothesis or MEH. The Market Engagement Hypothesis identifies the key belief or assumption about how the market will engage with your product or idea.

So how does it work? Well, let’s take an example. Suppose you want to sell socks with different logos of cryptocurrencies: CryptoSocks. Why would people buy from you?

Perhaps your hypothesis is: If we put cryptocurrency logo’s on socks and make them as colorful as Happy Socks, many people who own cryptocurrencies are willing to buy socks with their favorite cryptocurrency logo on it.

This sounds pretty good, but it’s not very specific yet. So after creating this initial hypothesis, the next step is to create a so-called XYZ Hypothesis: At least X% of Y will Z.

In this case, perhaps we hypothesize that at least 5% of all cryptocurrency owners will want to buy CryptoSocks.

A third step, is to take this XYZ Hypothesis further and hypozoom (yes, the author is quite a fan of creating his own words). With hypozooming, Sevoia means to say that you create an even more specific and zoomed-in hypothesis that you can test right now.

For instance, we could say that at least 5% of cryptocurrency owners in my hometown Utrecht, will want to pay €5 for a pair of CryptoSocks. With this zoomed-in (or hypozoomed) Market Engagement Hypothesis, I can actually start gathering data and find out whether CryptoSocks are a good idea or not.

No MVPs, no Prototyping — But Pretotyping

So, how do you do this? Well, with a pretotype. Another made-up word, a pretotype is not the same as an MVP or prototype. Rather than being functional (as an MVP often is) or a catch-all concept (as a prototype is), a pretotype is a fake or mocked-up version of your intended product or service.

The goal of any pretotype is to validate quickly whether it’s worth it to pursue your product or service idea. So let’s apply that to our CryptoSocks.

In software development, it is quite common to whip up a landing page for a product without actually selling that product. For instance, I could create an online page for our Cryptosocks, with one ‘buy button’ for everyone’s favorite: Bitcoin socks.

I would then send an email with the link to the page to all cryptocurrency owners in Utrecht I know — and see how many percent of those (that visit the page) actually press the ‘Buy Now’ button.

This is an example of a Fake Door pretotype which in software is often called a Smoke Test. Importantly, running this experiment would give me data that I created myself — Your Own Data!

The next step is to evaluate this data, and finally determine whether CryptoSocks are The Right It. But before we do that, let’s discuss some other examples of Pretotypes.

Examples of Pretotypes

This Fake Door is just one example of a Pretotype; there are many others. The idea of a Pretotype is always to test your (hypozoomed) hypothesis in a quick-and-dirty way, to validate whether you’re building The Right It.

Consider for instance these Pretotype Examples:

- The One-Night Stand Pretotype (offer something very briefly – e.g. Airbnb founders renting out an air mattress for the night)

- The Infiltrator Pretotype (place your product in someone else’s sales environment – e.g. leave a kitchen utensil in IKEA and see how many people buy it)

- The Relabel Pretotype (put a different label on an existing product and put it in front of a user – e.g. a fake book cover)

- The Live Demo Pretotype (give users a live-but-fake demo of your product/service)

- The Morsel Pretotype (provide a sample of the full product, e.g. a sample chapter of a book)

But there are many more such as the Mechanical Turk Pretotype, the Pinocchio Pretotype, the Fake Door Pretotype, the Facade Pretotype, and the YouTube Pretotype.

On his website, Savoia provides an interesting overview of more examples.

The Right It (TRI) Meter

So with that in mind, let’s move to the last step. After creating the pretotype and running the test, how do you determine whether your idea is actually something worth investing more time and money in?

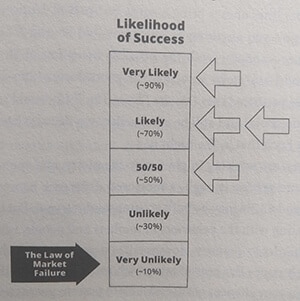

We use the TRI Meter. The Right It Meter is a tool used to interpret your data as objectively as possible. Specifically, it consists of different boxes, each with a ‘likelihood of success’ for your idea to beat the Law of Market Failure.

Let’s go back to our CryptoSocks. We hypothesized that 5% of cryptocurrency owners in the town of Utrecht, will want to pay €5 for a pair of CryptoSocks. Suppose we created our pretotype and have our data.

In the end, we find that only 1% of people who landed on our page pressed the buy button. Now we ask ourselves: If only 1% of cryptocurrency owners (in Utrecht) want to buy our socks, how likely is it that our idea is The Right It? On that basis, you point an arrow to the right box in the TRI Meter.

In the case of CryptoSocks, I think ‘Unlikely’ or a 30% chance is fair.

But it doesn’t stop here! You need to run a few experiments to really determine whether your idea is an investment worth making. Preferably, we tweak our idea a little bit (perhaps we create ‘TechSocks’ rather than CryptoSocks), create a new pretotype, and run a new experiment.

If all goes well, you can keep running experiments, tweaking and pivoting (in Lean Startup terms) until you’ve added several ideas to the ‘Very Likely’ box. Then, you truly know that the idea you have is The Right It.

Applying the Lessons of The Right It

Considering this summary of the book and all these pretotypes, there’s a lot to take in. So how do you apply the lessons of The Right It?

Actually, if you use the above steps, you’ve applied all the major lessons of this book:

- First, create a Market Engagement Hypothesis, then hypozoom, and create an XYZ hypothesis that is specific and measurable.

- Second, consider different types of pretotypes, as discussed above. What pretotype best fits your product or service?

- Third, set up your pretotype and run a first test.

- Fourth and last, consider your data and where it falls along the TRI Meter. On that basis, revise your idea or your pretotype and run another test. Keep going until you are (much more) confident that you’ve found The Right It!

In addition, you can check out the author’s lecture on YouTube, which provides another summary of the book.

The Right It Book Review by an entrepreneur

There are many books that give actionable advice to people who want to set up a business and do it right. From the Lean Startup by Eric Ries (and its build-measure-learn loop) to the Build Trap by Melissa Perri, the Lean Product Playbook (and its Problem Space and Solution Space), and many more.

In a way, these books look alike because just like The Right It, they all come down to one idea. The idea that you need to focus on a problem first (not a solution) — and that you need to stop theorizing and start actually testing your hypotheses and assumptions.

But despite the similarities between these books, the Right It is still very valuable. I particularly found the hypothesizing and hypozooming exercise intriguing. While I usually do write down certain hypotheses I’m working with, I hadn’t yet learnt to make these so specific or so quickly applicable. If you follow the steps in the book well, you can test a product idea really quickly, something that is not possible after reading The Lean Startup for the first time.

Similarly, the amount of pretotyping examples as discussed above was eye-opening. Testing your product with a fake landing page is incredibly common — but these examples show that there are many more ways to test whether your idea is (or could be) The Right It.

If you would like to read further buy The Right It book here. Want to read about other books for entrepreneurs? Check out my recent review of Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products.

Note that I only write about books that I’ve actually read and products I’ve actually used — this post contains an affiliate link from Amazon; as an Amazon Associate I may earn a small commission if you click and buy the product in question.

Recent Comments